The night of his graduation in 1962, Sandy Jamieson skipped the Great Falls (Montana) High School celebration parties, packed up a ’58 Studebaker and started the drive to Alaska with his two best friends. It turned out to be a one-way trip.

“We each sold our junkers, bought one car, and drove up here,” Jamieson said. “We all found lives we love and never left.”

For Jamieson’s generation, a journey like his up the Alaska-Canadian Highway was not an uncommon story. Alaska was popular in the public imagination; ?Johnny Horton’s “North to Alaska” was a 1960s hit as was the movie of the same name. Many who made the trek to the state in those years went on to lead adventurous lives — Jamieson among them.

What sets Jamieson apart is that his Alaska story is tied to one of the nation’s wildest, most remote places?—?the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Now, after 40-plus years as a hunting guide on the refuge, Jamieson is retiring. This will conclude a decades-long business relationship he’s enjoyed with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service).

It’s a tenure that began before the landmark Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act. The 1980 legislation expanded Arctic Range into the 19 million-plus-acre Arctic Refuge, a tract roughly the size of South Carolina.

He’s been more than a guide, too. Jamieson is an artist, cook and conservationist.

“Other places may have more dramatic scenery. Lots of them have a lot more game animals in them. But none of them have that sense of actually also going back in time to a different state of things in the earth. A different relationship between people and what we call territory,” Jamieson said of the refuge. “That’s something that I don’t think, especially the eastern portion … that is that much of that sense, that sense of being a part.”

Jamieson is eager to show others what he discovered all those years ago, said Steve Berendzen, who manages Arctic Refuge.

“The wildness of Arctic Refuge is part of Sandy’s pride in place,” Berendzen said. “He is passionate about sharing that with his hunting clients; conveying that this wild land is a full community that includes every little plant, the animals, as well as the people.”

Jamieson is a self-described “fan of the refuge idea.” He appreciates how user-friendly Arctic Refuge and other refuges are for a range of people, especially hunters. He knows his conservation history and can thoroughly explain how hunters have been instrumental in funding wildlife management and research, and restoring game populations.

But his broader interest, Jamieson says, is “to help people appreciate game animals as a way to connect with wildness; that hunting and harvesting are not separate from daily life and how we take care of our bodies.”

He hopes that the renewed focus on local foods and what appears to be a limitless interest in cooking shows can help.

“I’m more of a cook and a social hunter,” said Jamieson, who’ll happily share his recipe for moose roast. “I appreciate the company of other hunters and I very much appreciate being able to share the meat and host people for nicely prepared dinners.”

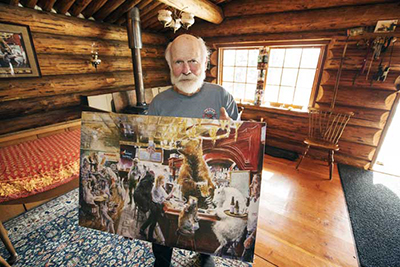

Jamieson also believes one of the best ways to connect more people to refuges and wildlife is through art. He is well-known throughout the state, and especially in his hometown of Fairbanks, for paintings that juxtapose wildlife in human surroundings.

Deb Hickok, President and CEO of Explore Fairbanks, is a fan. “Sandy is not only a remarkable artist and crafts person but he’s also a remarkable person,” said Hickok, who heads a nonprofit marketing organization that promotes Fairbanks events and attractions. “His art reflects our Alaska lifestyle demonstrating the full charm of our collective quirkiness.”

One of her favorites: “Wildlife Refuge,” in which a bear tends bar while other creatures, two- and four-legged, gather for a drink or two. On a website, he describes the painting depicting a place where “the age-old struggle for survival in our beautiful and harsh wilderness can be set aside for a time.”

“I’m fairly certain animals all have distinct personalities, just like people do,” Jamieson said. “It’s fun for me to use that and try to and sort of teach that by putting them in the place of humans, especially since humans tend to be highly judgmental about animals; I just like to get up their noses about that a little bit.”

Later this summer, Jamieson will head back to Arctic Refuge to share his four decades of knowledge with the company taking over the area where he was permitted to guide.

The first thing he’ll tell them: “Consider the old guys you have around camp.” And this: “Some of my best neighbors out there have been animals.” Remember, he said, repeating a line of poetry he wrote years before to accompany one of his paintings, “when it comes to the need for truly wild places, we are all in the same boat.”

Sign In

Sign In

Sign In

Sign In