The past may be dead and gone—but that notion doesn’t fly here on the Vermejo Park Ranch. Managers of these 585,000 acres have returned elk and bison to the peaks and plateaus of one of the nation’s largest private ranches and top outdoor vacation destinations. The prairies are, once again, home to endangered black-footed ferrets.

And, most recently, long reaches of mountain streams have been restored for the benefit of a remnant population of Rio Grande cutthroat trout—and the guided anglers who seek to catch the rare native fish.

Ranch employee Lief Ahlm’s decades of native fish conservation experience made him a natural fit for this latest endeavor between the (Ted) Turner Enterprises-owned ranch and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service).

The biologist originates from the northwest corner of the state, and got educated in fisheries science at New Mexico State University. He followed that with a long and fruitful career with the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish. “I had a front-row view of some of the greatest conservation work in New Mexico,” said Ahlm, speaking toward the many projects that he worked on through the decades: big horn sheep and pronghorn transplants, and law enforcement.

But his heart’s desires lie with fish conservation. Ahlm managed the famous San Juan River trout fishery for a time and was involved in native fish conservation endeavor in all corners of the state. And his heart—still in it—led him to improve habitat for rare trout on the Vermejo Park Ranch, a step that in the end can help keep this fish off the endangered species list.

“The cutthroat trout in these streams are holdovers from another time—and they have survived an onslaught of habitat loss and competition with introduced brook trout native to Appalachia,” Ahlm said.

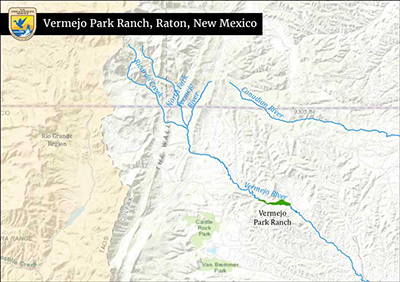

The headwaters of the Vermejo River trickle over the Colorado state line into New Mexico and the storied Vermejo Park Ranch. This is the heart of the historic Maxwell Land Grant—where the southern Rockies meet the prairie, and where the Rio Grande cutthroat persists.

The northern New Mexico watershed looks like a cartographer laid a turkey’s foot on paper, traced it, and made it into a map. Three rivulets, the “toes” of the turkey foot, flow south to meet in an open vega—a big meadow—hemmed in close to the east by a steep, craggy stone wall the color of a pronghorn’s pelt. Ponderosa pine trees stretch from the rock crevices. It is steep and imposing.

On the other side, the slope fans westward, gently, then precipitously to 11,000-foot purplish peaks that typify the southern Rockies.

The remains of last winter’s snows tip the peaks like dollops of thick cream. That snow is future trout habitat when it spills off the mountainsides and percolates over gravelly riffles and purls through dark pools.

The cold, clear waters of the turkey foot—the North Fork, Little Vermejo and Ricardo creeks—hold an aboriginal population of Rio Grande cutthroat trout, unique to the headwaters of the Canadian River drainage, Ahlm said.

These fish have immeasurable intrinsic value, an artifact of an epoch past. The Rio Grande cutthroat was the first trout documented in the New World. In 1541, a chronicler of the Coronado expedition noted truchas—trout—swimming about in a tributary to the Pecos River as the explorers made their way toward Kansas.

The cutthroat subspecies persists in only 10 percent of its natural range: the upper Rio Grande basin, the upper Pecos, and the furthest reaches of small Canadian River tributaries. The fish retreated to small headwater streams due to habitat lost to overgrazing and a century of competition with nonnative trout species.

They exclude deer, elk, and bison from certain stream banks so vegetation regrows, nourishing trout habitat. Since 2014, 10 half-mile-long blocks of stream have been rested from grazing by fencing off more than a dozen collective stream miles.

“Teaming up with the Fish and Wildlife Service allowed us to do the work faster and bigger with expanded intellectual power,” said Carter Kruse, director of natural resources for Turner Enterprises. “By ourselves, we’d still be on exclosure number-three.”

The outcome is impressive to witness. Ahlm explained that the stream channel narrows, allowing the water flow to scrape deeper pools for the trout and the bugs they eat. Plantings of cottonwood along the stream help stabilize the bank and add shade, he said.

“The fenced areas have seen a profusion of willow growth, shading and cooling the water and stabilizing the stream banks. That’s good for trout,” Ahlm said. Long-term monitoring, according to Vermejo’s natural resources division manager Les Dhaseleer, should reveal progress in water quality and aquatic insect composition along the length of the Vermejo River through the ranch.

Once these half-mile sections heal, fencing will be moved to rest adjacent stream sections. It’s a long-term affair. In the end, it should yield quality habitat for trout and other species. It may even become home one day to the endangered New Mexico meadow jumping mouse.

“The magnitude of the overall project and the landowner’s commitment to conservation will benefit cutthroat trout and other wildlife for decades,” said Service biologist Montoya.

At Vermejo Park Ranch, that future blends with history.

Not far from the stream restoration work are important landmarks for wildlife enthusiasts and for Ahlm, who holds a personal affinity for New Mexico history: the Elliot Barker State Wildlife Area and the cabin where the legendary conservationist, his wife and two young daughters lived for a time.

Barker cared about the native trout of this region probably as much as Ahlm and his colleagues. He worked under the auspices of his Forest Service supervisor Aldo Leopold in the 1910s. After working for Vermejo Park Ranch as a game manager in the late 1920s, Barker went on to serve as director of the Game and Fish Department for 22 years. He published seven books on conservation and western life, and died in 1988 at 101.

With Ahlm on career number two at Vermejo Park Ranch, the two men intersect in spirit. “You can’t help but feel a kinship to Barker out here,” said Ahlm. “He and I both worked for the same outfits, and I suspect that working here influenced his conservation ethic and the progression of his long career. It’s kind of cool,” he said, as he passed through a gate of an exclosure where ranch employees were busy augering holes for cottonwood poles near the spur of the turkey foot.

Mere feet away Rio Grande cutthroat trout, followed by their silent shadows, threw up puffs of sand as they scurried for the cover of grass thickets that hang over a cut bank.

Sign In

Sign In

Sign In

Sign In