The Direction of Land Conservation in the 21st Century

By: Amos S. Eno

Posted on:07/27/2015 Updated:01/09/2018I spent the later half of last week in Boise, Idaho, where I gave a speech as part of the Joint State Conservation Summit hosted by the Idaho Soil & Water Conservation Commission. Below is an abridged version of that speech.

The west today, which few realize, is the most urbanized section of the country with two or three large metropolitan areas dominating each western state (think Boise, Pocatello). Ironically, “the modern American West, for the nation’s most open and empty region, is also the most heavily urbanized.”[1] “One out of every four Americans now lives in a western metropolitan area, up from one out of eleven in 1940.”[2] By 1990, 80% of Westerners lived in metropolitan areas ranging in size from:

- Boise, ID (205,671)

- Casper WY. (55,316)

- Salt Lake City, UT (186,440)

- Billings, MT (104,170)

- Phoenix, AZ (1.5m )

- Denver, CO (600,158)

- Seattle-Tacoma, WA (807,057)

- Los Angeles-Anaheim-Riverside complex with its 18,550,288 people.

Roughly half of the rest live in small towns, leaving only one westerner in ten for the “real West” of farms, ranches and forested landscapes. Needless to say the population of the rural West does not have the votes or the political muscle to control its destiny in our contemporary political environment.

Today, 30-70% or more of each western state is now in public ownership as part of the four federal conservation agency portfolios. Idaho, for example, is only 20% private lands. One of the starkest, dysfunctional realities of our western commonweal is the steep value divide between the metropolitan West and the slightly populated rural areas of ranches occupying river valleys and prairies.

This value chasm between these two politically parallel and ecologically connected communities is deeper than the deepest recesses of the Grand Canyon or Hells Canyon. Of course the metropolitan west links up with the metro areas of the eastern and Midwestern states in contemporary political decision making in Congress and the Executive Branch, affecting western lands. So let us get our priorities straight and make our investments where they are needed. We do not need to keep buying public lands in the west, but we do need more expansive recreation infrastructures in our expanding metropolitan areas.

Last month I visited Lemhi Valley, ID in the eastern part of this state. Home to the Lemhi river and the furthest and highest reaches of the Columbia/Snake watershed where chinook salmon spawn at over 6,000 feet after climbing through eight major dam complexes. Lemhi Valley has seven times as many cows as people.

A decade ago the Lemhi Regional Land Trust was incubated by 4 ranchers and today is the embodiment of community conservation as this ranching community is aggressively conserving both the landscape and the human community that resides precariously in this remote region. In the past two decades the most successful land trusts in the west, and I am including Texas, are cattleman/ag land trusts such as California Rangeland Trust, Colorado Cattleman’s Ag Land Trust, Texas Ag Land Trust, and Lemhi Regional Land Trust.

Idaho needs a state-wide Cattleman’s Ag Land Trust…Anyone interested in jump starting this effort should contact Laurel Sayer at the Idaho Coalition of Land Trusts, laurel@idaholandtrusts.org, (208) 521-2987.

The first three are now the largest land trusts in their respective states, and as their easement portfolios expand to 100,000 acres and more these land trusts need stewardship funding. This should be a priority for LWCF funding! Why?

First, because it is cost effective. Look at our federal conservation lands today: they host a $35 billion backlog in deferred maintenance. Stewardship funding needs represent just 1/70th of that expense.

Second, because private lands are the lifeblood of the west and are 5 times more important than private lands anywhere else in the country. Why?

- Because they control the water that flows to our metropolitan areas- the waters that sustain Los Angeles flow from private land watersheds

- They host all our transportation corridors.

- They host the sighting of all new energy infrastructure

- They host all our biodiversity, the preponderance of our fish, wildlife, both game and nongame species.

- They host the vast majority of both wetlands (70%) and endangered species habitats (75%).

Do you want to spend millions of federal dollars acquiring more public lands in the face of $17.8 trillion in national indebtedness (equates to $44,900 per person U.S. population), or spend a tiny fraction of those sums to protect the lifeblood of the west through cooperative conservation involving the human legacies of our western heritage?

Reforming the Endangered Species Act is a hot topic in Washington and among members of Congress. A number of environmental groups (Center for Biological Diversity, Defenders of Wildlife, Wild Earth Guardians) have hijacked the Endangered Species Act (ESA) pushing species listings at the expense of species recovery.

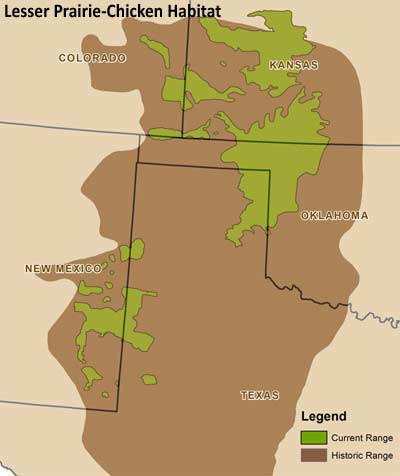

Recent listings include the lesser prairie chicken (listed as threatened, May, 2014) found in 5 plains states (TX, NM, CO, KA, OK) where its habitat is 95% on private lands, the Gunnison sage grouse (listed as threatened Nov., 2014) in SW Colorado and SE Utah, the long eared bat which inhabits 38 states predominately private land, and the greater sage grouse found in 11 western states with a FWS decision pending in September 2015. All of these species are found primarily on private lands where FWS has limited to no capacity to provide for recovery of the species in question…

Recent listings include the lesser prairie chicken (listed as threatened, May, 2014) found in 5 plains states (TX, NM, CO, KA, OK) where its habitat is 95% on private lands, the Gunnison sage grouse (listed as threatened Nov., 2014) in SW Colorado and SE Utah, the long eared bat which inhabits 38 states predominately private land, and the greater sage grouse found in 11 western states with a FWS decision pending in September 2015. All of these species are found primarily on private lands where FWS has limited to no capacity to provide for recovery of the species in question…

We need a comprehensive, scalable solution that brings us back to the original intention of the Endangered Species Act: bringing about species recovery. And the answer lies before our very eyes…

Today all states actively participate in species recovery, often dwarfing federal efforts by comparison. Nothing better exemplifies this on the ground reality than the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (WAFWA) recovery plan for lesser prairie chicken…

In one year of implementation the WAFWA recovery effort has raised $46 million for LPC recovery from 181 corporations which have set aside 11 million acres of land and WAFWA has recently enrolled 97,000 acres of long term (10 year) easements in priority habitat areas, and recently enrolled 1600 acres forming the new Yoakum Dunes Wildlife Management Area in the Texas Panhandle.

Comparable efforts are being under taken by states for the Gunnison and greater sage grouse. In Gunnison County, CO. 97% of the private lands are enrolled in conservation agreements and the county is the only county in the U.S. with a dedicated wildlife biologist on board, an ex-FWS-er at that!

In Utah, the Utah Watershed Restoration Initiative (WRI) has completed 1,340 projects, treating over 1.15 million acres of habitat with an investment by all partners of over $130 million. In 2014, with a special appropriation from the Utah legislature, WRI completed 130 projects, restoring 112,987 acres of uplands (including conifer removal for sage grouse) and 55 miles of stream and riparian areas.

Consequently the focus of Endangered Species Act reform should not be on restricting listing, or legislative riders to prevent or delay listing, but on expanding Section 6 of the Act to empower the states: get them into the game earlier at the pre-listing and candidate species level, and to triple or quadruple the funding awarded to states to enable recovery actions through the Cooperative Endangered Species Fund. This is consistent with the original intents of the act which

“declared to be the policy of Congress that all federal department and agencies shall seek to conserve endangered species and threatened species and shall utilize their authorities in furtherance of this Act. (2) It is further declared to be the policy of Congress that Federal agencies shall cooperate with state and local agencies to resolve water issues in concert with conservation of water.”[3]

Speaking of water, low and behold, the west and plains states have had rain the past two springs. Viola’, despite the doomsday predictions of environmental litigants for species listing, the lesser prairie chicken population rose last year by 20%, and this year by 25%. I expect comparable gains for sage grouse as both these species are drought adapted species living in regions with notoriously erratic rainfall regimes.

The portal for Endangered Species Act reform is through Section 6 and empowering states to do the hands on job of on- the -ground recovery.

The twentieth century was dominated by ever increasing expansion of our public lands portfolio at the federal, state and non-profit levels, but private land conservation is and will be the conservation market of the 21st century, even if the environmental community at large has not figured this out yet.

Our existing public conservation land portfolio does not protect biodiversity. I learned this graphically through work pioneered here at University of Idaho by Michael Scott and colleagues who developed GIS/GAP technology that allows us to correlate between land conservation strategies and the hotspots and areas where species richness predominates. What do we find? Most federal land is over 3000 feet. We are protecting rocks, ice, alpine trees, and high-altitude deserts in abundance. Meanwhile, the biodiversity is concentrated in our creeks, drainages and river bottoms (Snake, Salmon, Lemhi) throughout the west, which is predominantly in private ownership.

Despite the preponderance of public lands in the west, private lands therein are 5 times more important than anywhere else in the nation for one simple reason: they control the water. Thus they are our reservoirs of biodiversity; they supply waters to our metropolitan areas, they host our agriculture, and they are the corridors for transportation and energy build out.

Despite the preponderance of public lands in the west, private lands therein are 5 times more important than anywhere else in the nation for one simple reason: they control the water. Thus they are our reservoirs of biodiversity; they supply waters to our metropolitan areas, they host our agriculture, and they are the corridors for transportation and energy build out.

I can’t give a speech without reference to Aldo Leopold, who way back in the early 20th century presciently wrote in his River of The Mother of God essays

“the geography of conservation is such that most of the best land will always be held privately for agricultural production. The bulk of responsibility for conservation thus necessarily devolves upon the private custodian, especially the farmer.”[4]

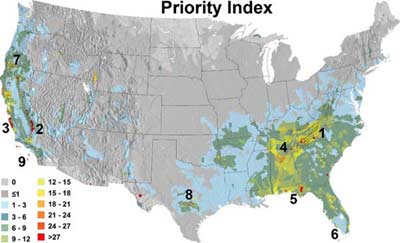

A recent study released this past spring (PNAS, March, 2015) by Clinton Jenkins et al. only further underlines my two decade long promotion of focusing conservation on private lands[5]. As the image demonstrates, the priority areas for protecting biodiversity in the U.S. are primarily in the southeast which is overwhelmingly private land with a slim corridor on the west coast, particularly California.

A recent study released this past spring (PNAS, March, 2015) by Clinton Jenkins et al. only further underlines my two decade long promotion of focusing conservation on private lands[5]. As the image demonstrates, the priority areas for protecting biodiversity in the U.S. are primarily in the southeast which is overwhelmingly private land with a slim corridor on the west coast, particularly California.

It is time we stop reacting like lemmings to environmental hysteria and look at the tools in our quivers of public policy and incentives for conservation, as those are the drivers of human behavior. My Advisory Board member Rick Knight at Colorado State University has written “that for conservation to work, it must harness three dimensions – the human one, the economic one, and the ecological one”[6]. In my opinion, for several decades we have over emphasized the ecological to the exclusion of the human and economic dimensions, which now need to be brought to the forefront of policy.

Most ranchers in this part of the world, and private land owners generally, and the businesses that cater to land owners are small businesses… Small businesses are core to America’s economic competitiveness. Not only do they employ half of the nation’s private sector work force – about 120 million people – but since 1995 they have created over 60% of the net new jobs in our country.[7]

The demographics of land owners are even steeper than the general public, and we are witnessing dramatic changes driven by demographics alone, a “seismic shift in age distribution will affect spending and technology patterns…the baby boomer generation, or those born between 1945 and 1964, is starting to move to retirement – and fast. About 10,000 new baby boomers retire every day, and Pew Research estimates that 10,000 will cross that threshold every day for the next 19 years.”[8]

Land owners respond better to tax incentives than to regulatory impress. The most important tax initiative on the horizon is the Conservation Easement Incentive Act (s. 330), which makes conservation easement tax deductions, first signed into law by President Bush in 2006, permanent!

This tax reform has led to a 300% or more increase in easements during the years it has been available. Out here in the west where ranchers like those in Lemhi Valley tend to be land rich, cash poor, these tax incentives provide an enormous boost for conservation. Western metropolises are expanding outward. Companies like Simplot recognize that development of farmland poses a real threat to the future of agriculture in states like Idaho. Easements allow working landscapes of farm agriculture and forests to keep working. Passage of this small tax provision will do more for conservation nationally than fully funding the LWCF by several factors of magnitude.

If we utilized the tax code for comparable innovations for irrigation and water management and to encourage recycling we might also get off ground zero in the West.

How do you deal with everything I have talked about in one fell swoop, at least from a land owners’ perspective? At LandCAN, we are creating state-wide hubs of Conservation Connectivity. Go to our Idaho Conservation Connection, www.stateconservation.org/idaho, and you will find all the federal programs such as USDA’s Farm Bill, USFS Stewardship, and FWS Partners Program. We also host information about the Sage Grouse Initiative that assists private land owners across all eleven western states. Additionally we provide access to the state funding and technical assistance programs, all the non-advocacy non-profits working with land owners such as the soil and water conservation districts, land trusts, like Lemhi Regional Land Trust, orgs such as the Idaho Coalition of Land Trusts, and thousands of for profit businesses- such as tax and estate attorneys, veterinarians, grazing consultants serving the rural, ag and private land owning community. We provide you the conservation equivalent of your smart phone.

If we have learned anything in the last 40 – 50 years on a world-wide basis, it is that the closer you design conservation projects to the community level, in conjunction with native or local people as integral elements of any project, the better the result.

LandCAN serves as the US foundation for Wilderness Safaris, and its conservation unit, Wilderness Wildlife Trust (WWT). It is the best eco-tourism company in the world. Wilderness has some 80 camps across nine African nations, and is protecting over 8 million acres of Africa’s prime wildlife habitat, more than three times the size of Yellowstone.

Wilderness Wildlife Trust’s Botswana Rhino Reintroduction Project recently moved nine rhinos from Kruger National Park in the Republic of South Africa where they are being poached silly, to Wilderness areas in Botswana.

This is a private sector company that works with local communities to implement long-term conservation and provides the underpinning for community economic sustainability.

Here in the US, the more we can move both decision-making and on the ground implementation down a step from Washington to the state level, the better the local and community involvement in conservation initiatives will be.

In today’s world, states are the laboratories of conservation innovation and the enablers of on the ground conservation initiatives. This is no surprise as over the past several decades many states have tightened their belts in contractions of fiscal discipline, something wholly lacking at the federal level. We need to build on the successes of the states customizing local conservation efforts as we move through 21st century conservation policy and implementation.

Community-based conservation is taking hold world-wide, for the US to maintain its traditional position as the band leader in the front of the conservation parade, the more we can do to empower state-based leadership and design the better.

Every state is different in terms of culture, geography and natural resource portfolio. The Washington approach of one-size-fits-all and formulaic grant allocation has been demonstrably proven to be out of date, out of fashion, and a failure! It is high time we look to state leadership in conservation for our wildlife and our land.

[1] Carl Abbott, The Metropolitan Frontier: Cities in the Modern American West(Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 1993), 11.

[3] Endangered Species Act, 16 U.S.C. § 1531 (1973).

[4] Aldo Leopold, introduction to The River of the Mother of God: and other Essays by Aldo Leopold (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1991), 22.

[5] Clinton N. Jenkins et al., "US protected lands mismatch biodiversity priorities," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112, no. 16 (April 21, 2015).

[6] Richard L. Knight, "Combat Biology: Time to Practice Conservation That Works," Range Magazine, Summer 2015, 40.

[7] Karen Mills and Brayden McCarthy, “The State of Small Business Lending: Credit Access During the Recovery and How Technology May Change the Game,” Harvard Business School General Management Unit Working Paper No. 15-004.

Sign In

Sign In

Sign In

Sign In