Pacific NW Coached Stewardship Planning: Longterm Investments

By: Amos S. Eno

Posted on:12/08/2010In Oregon and Washington, coached Forest Stewardship Planning is an investment, not only in forests, but in the people who care for the land.

Today,

in followup to the recent post describing the national goals of the Forest Service’s Forest Stewardship Planning (FSP) Program, I’m focusing on FSP for private forest landowners in the Pacific Northwest.

in followup to the recent post describing the national goals of the Forest Service’s Forest Stewardship Planning (FSP) Program, I’m focusing on FSP for private forest landowners in the Pacific Northwest.

You could be forgiven for asking, how important is a program for private forest landowners in the Pacific Northwest, home to 17 national forests? The answer is: very. Here’s why:

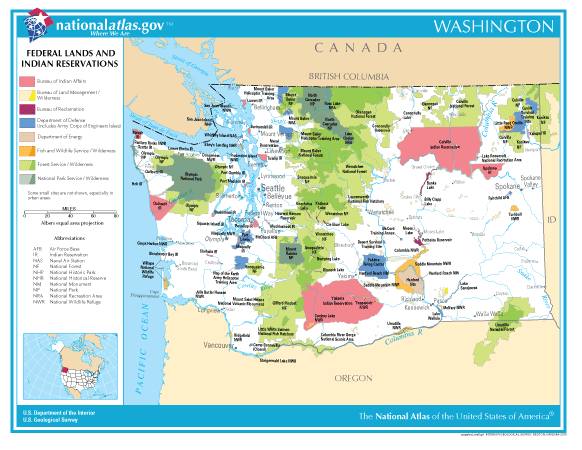

- Though public lands make up the majority of forest land in both states, private nonindustrial forests comprise 23% and 29% of the forest land base in Oregon and Washington, respectively.

- Timber from family forest lands has increased in importance since the mid-90s when their harvest levels started exceeding that of national forests.

- Like all forests, privately owned ones provide far more than simply timber - wildlife, water, and clean air to name just three - and throughout the West they are often key to connecting protected public lands because of their location in the lowlands, where most settlement has occurred.

- As in much of the U.S., both states are losing private forest lands to housing development.

- Private forest lands play a critical role in federal, state, and private efforts to bring back salmon. Each year, salmon must make their epic spawning journey from the ocean back to their natal streams in the higher altitude national forests. But to get there, most must pass through zones of private land that separate the sea from the mountains.

The Forest Service FSP ProgramRay Abriel is the Forest Service Regional Manager for Landowner Assistance in the Pacific Northwest. He recently told me, “We feel very strongly that assisting private landowners with management planning for their property is one of the most important things we can do. It helps them clarify their objectives for their forests, and if you want to drive from point A to B, you need a good map to get you there.”

But how important is this planning to landowners? It’s the key to funding - to qualify for lower county tax rates or for federal cost-sharing. Beyond that, landowners must understand and “buy in” to their plans if longterm stewardship benefits are to accrue. “Our answer,” says Abriel, “is to involve landowners in a process called ‘coached planning.’”

The Washington State Forestry ConsultantsWorking closely with state and federal agencies, Andrew Perleberg is an Extension Forester with Washington State University. Perleberg

helped to create coached planning in the early 90s. He says it removes forestry educators from the “here’s how” role and turns them into consultants helping landowners to define what they want.

“Coached planning involves nine weeks worth of formal classroom learning, taught by experts from foresters to soil scientists, along with field trips to each landowner’s property. Our goal is for every student to become the expert of his or her own property,” concludes Perleberg.

The Private Landowner’s StewardshipDave Konz, who took Perleberg’s class 10 years ago, is an exemplar coached planning grad. With his sister and their parents, he runs the

K Diamond K Ranch in eastern Washington: a 1600-acre dude ranch with about 1200 acres of timber.

“Before I began the process, we had ou

r timber cruised (value estimated). That little bit of knowledge helped me a lot. The coached planning hit every aspect of forestry and how to manage your timber,” recalls Konz.

“What did I start doing differently as a result of my management plan?” Konz echoes my question. “I had to intensify my thinning practices. The previous method I’d been using to harvest firewood and timber would only get a couple of hundred acres done over the long haul. Meanwhile, our biggest fear is wildfire. We realized we needed to hit the forest hard to create a fire boundary on our property lines adjacent to the Colville National Forest.

Dave says their forest is now growing more cords of wood each day than he can harvest. “I’d say we’re probably growing about six cords a day, and I take out an average of one a day.” Has the rate of growth increased since thinning? “Yes,” says Konz, unhesitating, “If you do nothing, about half of your trees will die. I’ve seen some trees 50 years old that are only five to six inches in diameter!”

Konz points out that his management has also become more intensive. In the past 12 years, some places have required treatment three to four times. “There are certain areas we really want to make into a park-like setting,” says Konz. “Aesthetics are very important. To make it more beautiful, you remove debris and plant native grasses to benefit wildlife. In turn, wildlife have become more abundant than in the years prior to thinning: deer, turkey and moose have moved in.

Unfortunately, over this same time period, the quality of the national forest land bordering Dave’s property has not improved. “They’ve done a little prescribed burning, but they don’t have the resources to do what they’d like. I’ve taken tours up to our property line and shown people what happens with and without proper management.”

Dave supports some prescribed burning, but would like to see more thinning. “Our county has the highest unemployment in the state of Washington, so why not create jobs? A good example of this approach that I’ve seen is at the Colville Tribe Indian Reservation. They’ve created jobs, extracted timber, and improved the health of their forest. I’d like to see more of this on the national forests.”

Sign In

Sign In

Sign In

Sign In