Beyond Rocks and Ice, More from Mike Scott

By: Amos S. Eno

Posted on:10/19/2010 Updated:10/22/2010The first Great Depression and Dust Bowl resulted in great strides for conservation and stewardship. What about this time?

This is a continuation of last week’s blog post, which began my conversation with Michael Scott, the father of GAP analysis.

Between America’s national parks, national forests, and other zones of “rock and ice,” lie the fertile mountain valleys and migration corridors that are almost exclusively privately held. Mike says, “Don’t get me wrong. Rocks and ice are increasingly important in an era of climate change, as high elevation refugia. But we don’t have a protection system that captures the full geographical, ecological, and geophysical range of species.

“The most important tool we have for saving species in an era of climate change is the species’ own ability to adapt and evolve in response to changing conditions. If a widespread species can find refuge in only one area across its range, then that’s only one opportunity to adapt and evolve.” Nature rewards redundancy.

Our Shining American Example of Conservation on a Continental Scale

Mike points out there’s one place in America where we have protected areas that reflect a full range of species and their seasonal distribution in America. “We have a gold standard we can look to for guidance: the Joint Venture models for waterfowl, and now all birds. The JVs have established the science and funding necessary to secure habitat and to maintain viable populations of waterfowl and other migratory birds for future generations.”

“Amos,” he continue s, “you were the driving force behind the initial Partners in Flight meeting (a conservation program for songbirds) modeled after the waterfowl program. Now, with the Service’s Landscape Conservation Cooperatives, for the first time the feds have said ‘we’re going to think about managing landscapes along ecological lines rather than political boundaries.’ That is a positive step toward bringing focus onto the landscape and using research results to make a difference on the ground.”

s, “you were the driving force behind the initial Partners in Flight meeting (a conservation program for songbirds) modeled after the waterfowl program. Now, with the Service’s Landscape Conservation Cooperatives, for the first time the feds have said ‘we’re going to think about managing landscapes along ecological lines rather than political boundaries.’ That is a positive step toward bringing focus onto the landscape and using research results to make a difference on the ground.”

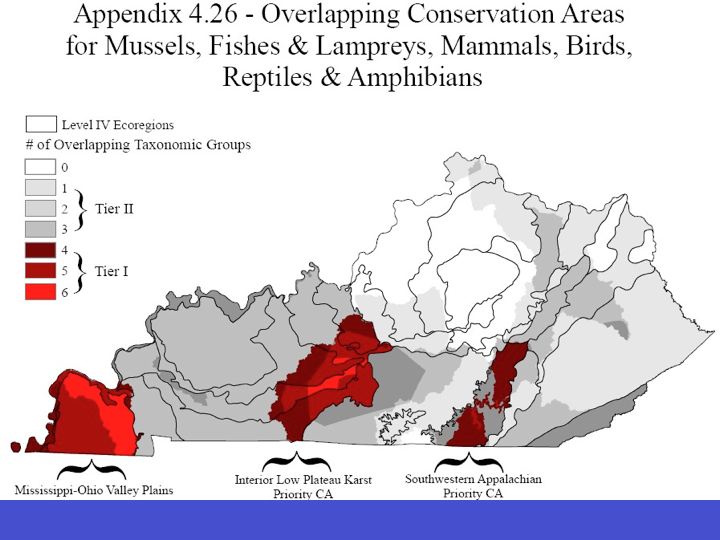

The state wildlife action plans now put more emphasis on keeping common species common, and GAP analysis is in wide use. The challenge today, Mike says, is in implementation: getting enough partners, engaging the private sector in a way that’s consistent with the business model and with maintaining biodiversity. “Multi-state efforts are the partnerships that work,” Mike says.

Barbecue Conservation? It’s Worked Before!

What does Mike Scott think is needed to ensure conservation occurs - at the magnitude necessary - in areas that are largely privately held? He answers, “Here’s a key metric: 5% of the public controls 90% of the private land. What would happen if every National Wildlife Refuge manager invited the 10 largest landowners to a barbecue to just talk - about what their needs are; how their needs do or don’t fit with refuge goals; how to implement state wildlife action plans? What if every governor invited the 25 largest landowners to regional barbecues in each state for the same pur pose?”

pose?”

“Private landowners have to make a living. If we continue to fragment the landscape and take land out of ranching and farming because they can no longer sustain a family, we’ll see more housing development in prime habitat and more barricades to migration. But where people are working together, we’re also seeing the reverse of that: barbed wire fences are coming down in Lava Lake and Craters of the Moon (Oregon and Idaho) to provide easier movement to pronghorn antelope!"

"Seven or Eight Species I’ve Known, Gone from the Planet"

“We’re in a transition period in which we’re seeing dramatic changes in economic models and the environment. You know when the biggest growth in the National Wildlife Refuge System occurred? It began in 1934, during the intersection of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl. Roosevelt worked with folks and put significant federal investments into the purchase of marginal agricultural land for Refuges, as well as the Civilian Conservation Corps for putting rural populations back to work restoring land.

“Those programs worked by finding the intersection of conservation and economic interests. The question is, where is that intersection today? Is it in coastal areas facing some of the greatest threats from sea level rise, storm surge, and loss of marshes and oceanfront property? Is it in non-native species? I think we have a huge opportunity, but the threat is not trivial. Seven or eight of the species I worked with in Hawaii are no longer on this planet. That’s a pretty tough challenge."

Private Lands: No Longer the Gap, but the Matrix

“I know people of all political persuasions, liberal, Republican, Democrat, libertarian, independent - who share the same values for wildlife and are working to make a difference. We need to focus on our shared values. I believe the biggest opportunity we have is in keeping common species common by involving the people in what I call ‘matrix lands’ that occur between protected areas. But we have to know where we’re going.”

Mike is very eloquent. I’ll end by noting that the “GAP” - the lack of protection - in his originally envisioned analyses, is now the “matrix” that holds everything together. Mike’s GIS GAP work provides irrefutable, technical, spatial, and biological data on the overwhelming importance of private lands for protecting biological diversity in the U.S.

There are a lot of people working on private land conservation. But it’s still an uphill battle against the demographics of our aging land-owning public, and the economics of sprawl, which gobbles up farm and forest open spaces. We have a compelling challenge on our hands, and we neglect the private land matrix at our own peril.

Sign In

Sign In

Sign In

Sign In