Wildfires Spread because Congress & Enviros ‘Can’t See the Forest for the Trees’

By: Amos S. Eno

Posted on:09/27/2012Veteran silviculturist urges Congress to assist the U.S. Forest Service in taking a proactive approach in fighting wildfires with common-sense, cost-saving preventive medicine.

Veteran silviculturist urges Congress to assist the U.S. Forest Service in taking a proactive approach in fighting wildfires with common-sense, cost-saving preventive medicine.

“This year provides clear evidence that the number one threat right now to the forests in the West is complete loss to wildfire. When a forest burns up, everyone and everything loses. We’re losing millions of acres to wildfires every year and that number is going up, while the associated burn severity is getting worse. If a house is lost in a wildfire, given a good home insurance policy, you can rebuild that same house in six months. But no matter how much money you spend or how many people you have, to replace an existing old-growth forest, to get it back to the functioning ecosystem that it was, will take you about 500 years. That is stark reality. Yes, you can replant/reforest a burned area and have that looking like forest cover within 20 to 30 years, but it is not the same ecosystem that was destroyed.”

That’s according to Rich Coakley, retired after 35 years with the U.S. Forest Service, “all of it in timber management, 25 of those years as a certified silviculturist, and all 35 years involved with fighting forest fires.”

This year Rich sat down for lengthy discussions with his northern California neighbor Peter Stent, a rancher with 800 acres of forest. (Read last week’s blog on “Rancher’s Zero-Cost Forest Management Plan” for details on Peter’s forest-thinning experiment, with before-and-after photos.) Together, they worked out a prescription for protecting Peter’s forestland from a catastrophic wildfire. This prescription called for:

-

Spacing: 16’ X 16’

-

Thin from below by removing the smallest diameter DBH [diameter breast height] trees first (eg. 1” to 8”)

-

Leave stumps at 6” to negate Fomes Annosus [root rot]

-

Do NOT cut any trees greater than or equal to 12” DBH . If these trees are found in clumps of twos or threes, leave them all

-

Do NOT cut, destroy or damage: Douglass Firs, Sugar Pines, Elderberry, Oaks, or Trees with two red bands painted on them

-

Do not remove any obvious, functioning snag trees

-

Pre-designate landings. Use existing ones or natural openings

-

Stay off of rock outcrops

-

Minimize impacts in the forest and on the ground

Rich emphasizes that “This was a custom prescription that met the owner's/Peter's objectives and the one that Peter opted to implement.” One of those objectives was to wind back the clock 100 years and mimic, with mechanical removal, what those “slow-moving low-intensity fires would have removed or inhibited from growing as they cleaned up the forest floor.”

“We had fire either from natural causes, such as lightening strikes, or the Native Americans would light it off because it facilitated their hunting and their protection. Those historical, frequent fires, that burned approximately every 10 years, kept the forest floor open, while leaving the trees above in an healthy growing, protected condition. The Native Americans had it right – they operated in sync with the environment,” Rich explains. “When we started putting all forest fires out as a national policy, at the time it seemed like a great idea – certainly to Smokey Bear and the public, but in retrospect, with all the evidence in front of us today, it was in fact a huge mistake. Much like building a dam without including an outlet at the bottom. Try holding that back for 100 years.”

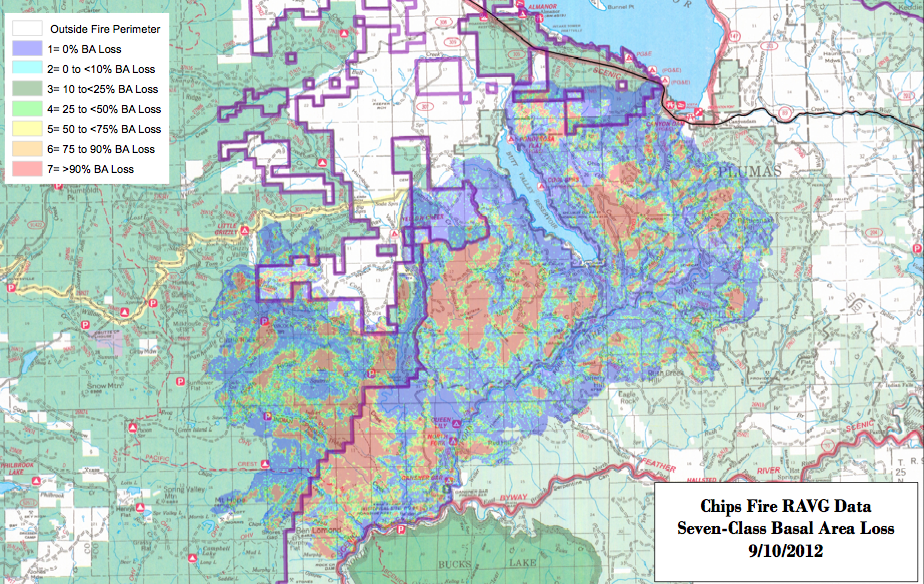

To illustrate the magnitude of that mistake, Rich points to maps of recent fires. For the Chips Fire that burned over 75,000 acres this summer, as shown in the map below, he says “It cost $55 million to fight that fire. Had the Forest Service been funded just half that amount, they could have thinned the majority of those same acres and prevented approximately 90% of the extreme damage and loss incurred by this wildfire. That’s just one example.”

Rich sees the maps as clear evidence of the value of thinning from below and removing ladder fuels: “Areas that had been designated for no treatment, including wildlife sanctuaries, went off like they got nuked. When that happens, everybody loses – the wildlife component loses, the taxpayers lose. It’s a sad situation that is preventable.” Pointing to the vast amount of acreage that is color-coded red, he says these areas “suffered major burn severity, a total loss of both young-growth and old-growth timber and the color-coded maps reflect that. A wildfire today doesn't care why any particular area was left untreated. It just knows it burns good, really good, no matter how many fire trucks or firefighters or helicopters or bombers are in the way.”

“It’s time for Congress to make some hard decisions,” Rich says. “Congress needs to realize that the U.S. Forest Service knows exactly what has to be done, they know how to do it, and they know where to do it based on existing fuel components, recorded fire history, and values at risk – not the least of which are wildlife habitats. With the support of Congress, the Forest Service can adopt and implement a much more proactive approach to address this current catastrophic situation by getting out ahead of what’s coming – wildfire – with thinning from below and post-thinning control burns. That Congressional support must come in the form of relief from existing environmental regulations and, more specifically, relief from required environmental documentation that currently keeps the Forest Service tied up in lengthy appeals and/or in court, wasting precious time and proactive opportunities. Only Congress has the power to allow the agency to operate at the scale and in the timely manner they need to operate. I’m not talking about commercial timber harvesting, nor am I advocating that every acre be thinned, but rather a large-scale, land-based, mosaic approach that prioritizes the potential for total loss to wildfire. Treat it like a fire before the fire takes place.”

“Without that critical support from Congress, without that paradigm shift in required environmental documentation and fire management approach, the National Forests of the West are doomed as they can only await their turn for total consumption by devastating conflagrations.”

Rich commends Peter for having the courage to “recognize the condition of his forests and the potential damage that he would sustain given a fire coming off the National Forest and on to his holdings. He has taken that first step in addressing the threat by taking care of his own property, while also providing for wildlife habitat.”

As for the environmental community, Rich suggests they follow Peter’s example. He believes most environmentalists “would get on board” to support sensible thinning and controlled burning “if they understood the ramifications.” Based on his own experience, he related that “If you take them out on the ground and show them the facts, the values at risk, the potential for total loss, the overwhelming majority of those folks see it and understand it immediately, but, unfortunately, most of them never make it out to see the devastating effects of wildfires.”

Because the West’s rampant wildfires are a matter of when, not if, Rich says “what Peter has done by thinning from below has effectively removed the ladder fuels, and, with that, he has taken the punch out of the fire when it comes. . . He has addressed the immediate threat, which is total loss to wildfire, and his forest stands that he treated are healthier because of that treatment.”

For Rich, “most private landowners love their trees, but don’t fully appreciate the greatest threat – wildfire. In effect, they can’t see the forest for the trees.” He says the discussion for these landowners, for Congress and for the environmental community needs to begin with the love of trees – and then expand into understanding that protecting these trees requires creating healthy forests which are “much more in sync with nature than their current untreated condition.” Better policy, he says, must be based on more people “understanding the ramifications, walking through these areas that were treated or were not treated, and understanding the treatment options.”

Rich warns that “if you’re a landowner, don’t sit down with someone with a vested interested in you the landowner cutting your timber.” He warns these operators “would log your property for their own financial gain without ever addressing the fire threat.” He advises “Your immediate concern as a private holder is total loss to wildfire. Address that concern. Thin from below and remove the ladder fuel. If you have to cut some commercial trees to pay for the thinning, then do so by removing the smallest commercial trees first and/or the larger trees that are obviously about to die, but maybe get a second opinion prior to starting. It’s not just pruning lower branches, it’s removing all that in-growth that has been allowed to come in, in the absence of fire for 100 years. If we were in sync back the way things were in the 1800s and all the years before that, you wouldn’t have that in-growth. It wouldn’t be there and wouldn’t be allowed to create that stepladder fuel effect that now carries these wildfires right up and into the crown of the old growth that never before was threatened in such a way.”

Rich concludes “We need to get fire back into the ecosystem without destroying everything, but to do that, the forests almost always need to be thinned first.” He adds that “the Forest Service also needs to be allowed to clean up quickly after a major fire by selling and salvage-logging the dead and dying timber. Quickly is the operative term. Again, the only body with the control over that is Congress. Without their support in the form of relief from lengthy environmental documentation, addressing associated appeals, and litigation, the Forest Service can do little more than spend their time and money in legal challenges. The result puts the agency at least a year or two down the road while the dead timber rots and degrades into a non-commercial product that then falls over and creates a tremendous fuel loading for the next fire.” As an example, Rich points back to the recent Chips Fire and explains that “about one-third of the total acres burned were a re-burn of a previous/older fire, the Story Fire. Those 25,000 acres were loaded up with brush and unsalvaged, burned-dead timber that had since fallen down and covered the ground, in some cases exceeding 40 tons per acre. When Chips hit that, it became the mother of all bonfires and impossible to stop.”

<><><><><>

Sign In

Sign In

Sign In

Sign In