Partners for Fish and Wildlife in Oregon

By: Amos S. Eno

Posted on:05/19/2011How partnerships help landowners and declining wildlife species at the same time.

CalLee Davenport, of the US Fish and Wildlife Service, went to Florida for his wife’s promotion 9 years ago. It’s only appropriate that she followed him back to Oregon when he was promoted to the position of Oregon State Coordinator for the Service’s Partners for Fish & Wildlife (PFW) Program about a year ago.

“I’m thrilled to be here in Oregon.” CalLee tells me. “Compared to Florida, there is so much more potential for a larger payoff by working with willing landowners here.”

The Service’s PFW program in Oregon has four primary habitat restoration priorities:

- stream and riparian restoration for Pacific steelhead, salmon and bull trout

- wet prairie restoration

- protection and restoration of oak woodland and savanna

- sage brush habitat and sage grouse population management

Seeing Things from a Landowner’s Perspective“In the Willamette Valley - originally mostly wet prairies - national wildlife refuges are managed to benefit a priority trust species, the Dusky Canada Goose, a Canada goose subspecies in severe decline. Problem is, a lot of landowners sometimes see the re

fuge complex as a burden because the refuge also attracts other, more plentiful types of Canada Geese. These geese historically migrated further south to the Sacramento River delta but are now stopping in Oregon - in far higher numbers and for a longer period of time. They find the farmer’s sod farms - of which there are many - delectable dining. So farmers ask ‘why should I restore wet prairie if its going to bring in more geese?’

“Our niche market in the Valley,” continues CalLee, “has become those owners who want to work with us to restore wetlands on their properties, and subsequently, acquire an easement. The selling point with the restoration is that many of the sod farmers can get a use permit from the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) through the

Wetland Reserve Program, and receive their NRCS payment plus the opportunity to get a grass crop off their property. If they get depredation, the easement has paid for that loss.”

The PFW program in Oregon also focuses on stream and riparian area restoration. Streams that have been diverted or modified for irrigation or other purposes have lost a lot of their value for many native fish species. Working with landowners and other cooperators, PFW revegetates riparian areas, eliminates stream diversions that are no longer in use, and removes blockages to improve fish passage and restore the historic channel. “Sometimes we combine a few of these approaches with breaching of dikes to rehydrate wetlands.”

“In oak woodlands,” says CalLee, “we have once again begun to concentrate on working with landowners to acquire permanent easements to help prevent future problems. Oak woodlands and savanna are definitely declining, and when a parcel

of oak woodland is purchased for development, inappropriate management can preclude natural or prescriptive fires and result in the overstocking of oaks and buildup of fuel loads. Restoration activities on these habitats include reducing invasives, reestablishing the native understory - including rare plants - and thinning of oaks while saving the heritage trees, which are so important to wildlife.

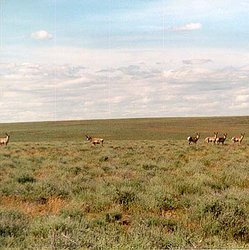

The last major PFW focus in Oregon is sagebrush habitat. The Greater Sage Grouse is a species that the FWS recently has found “warrants protection under the Endangered Species Act” and is therefore a focus of attention throughout sagebrush country. Overgrazing, energy development (wind and gas) and juniper invasion are the three major threats to sagebrush and the grouse. As with most ecosystems, threats to habitat can also translate into threats to those whose livelihoods depend on the ecosystem.

“Landowners love to

get rid of encroaching juniper, since it means more grass for their cattle,” CalLee says. “Grazing and creating Sage Grouse habitat are often compatible with one another and can be improved with rotational grazing methods. Encroaching juniper impacts sage grouse by providing perches for raptors, and predation can lead to lek abandonment. Juniper and other invasive species removal also decreases the risk of catastrophic fire.”

Alphabet Soup PartnershipsCalLee tells me that PFW works most frequently with NRCS, including their 11-state Sage Grouse Initiative, since NRCS has funding through the farm bill programs but, a lot of times, not enough infrastructure and personnel to get it out on the ground. “That’s where the Partners Program comes in. For PFW, some trust species components need to be there, or nearness to a national wildlife refuge or public lands.”

Landscape Conservation Cooperatives, or LCCs are part of the picture too. “Oregon includes parts of three different LCCs,” says CalLee. “The LCCs are roughly modeled after the waterfowl joint ventures and combine various governmental and non-governmental organizations, private landowners, and other stakeholders. Their role is to determine how best to put all the pieces together and use the collaborative LCC framework to get things done on the ground.”

An early example of an LCC-type initiative in Oregon uses the framework of NRCS’s

Cooperative Conservation Partnership Initiative. Approximately 30 different agencies and entities that have an interest in oak restoration have leveraged thei

r resources by putting together a future funding proposal. “If successful,” CalLee continues, “the CCPI will be funded through a national competition for Farm Bill funding. The Oregon CCPI proposal could provide funding for up to 150 landowners in the target area. NGOs such as The Nature Conservancy and the Klamath Bird Observatory are providing GIS and other monitoring activities. It is a true partnership, with everyone working toward the same end goal of restoring a very important declining habitat in Oregon.”

The Service is also working with landowners in Oregon to develop Candidate Conservation Agreements with assurances, or CCAAs. If landowners enroll in the CCAA prior to a species being listed, they will be given a permit containing assurances that if they engage in certain conservation actions for species included in the agreement, they will not be required to implement additional conservation measures beyond those in the CCAA, even after the species is listed.

CalLee and his staff are currently working to revamp the 5-year Partners Plan for Oregon - including how they will address other hot topics such as Spotted Owls and wolves.

Sign In

Sign In

Sign In

Sign In