Mike Scott, Father of GAP Analysis

By: Amos S. Eno

Posted on:10/14/2010 Updated:10/22/2010“The time to save species is when they are still common.”

This is the first of a two-part blog conversation about GAP analysis and the future of American ecosystems.

Mike Scott learned early in his career that a picture is, indeed, worth a thousand words. Mike began his first field research job in 1974, nine months after Nixon signed the Endangered Species Act. He was trying to answer fundamental questions about endangered birds of the Hawaiian islands:

- Do they still occur?

- If so, where?

- How many are there?

- What habitats do they prefer?

- What is the conservation status of the areas where they occur, and who owns the land?

Mike collected reams of data over eight years, and even wrote a book, but the feedback he kept getting from land managers was, to put it in his own words, “Where’s the beef?” Serendipitously, as with so many great scientific inventions, Scott hit upon an idea for conveying the significance of his research.

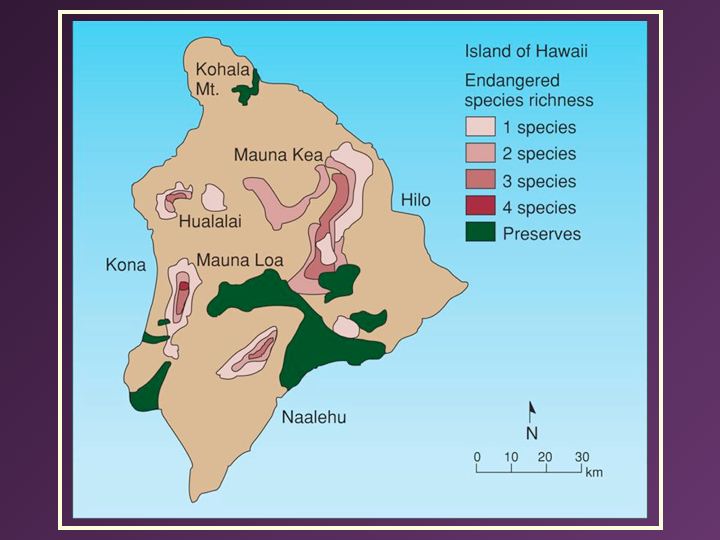

SerendipityDuring the course of a visit from one of his friends, who happened to be a geographer, Mike explained his problem. His friend said, “That’s pretty straight forward, we can use this new thing called GIS to show your results.” They sat down, “using mylar and crayons,” to create range maps for each Threatened and Endangered (T&E) species as well as blocking out protected areas in the state. “The disconnect,” Mike says, “was about 95%, with very little overlap between protected areas and priority habitats.”

“I still remem

ber my first presentation to state and federal agencies, including folks from The Nature Conservancy (TNC). One of the federal officials in attendance was dead-set against new protected areas. So I began showing one species map at a time, laying the disconnected protected areas on top, until finally the official shouted from the back of the room, 'Alright, Mike, I got the message!' The point was, protected areas at that time did not secure habitat for T&E species, and the GIS analysis put it in graphic form."

Through perseverance, continued refinement of the analysis, and some heavy-weight connections between a TNC staffer and Daniel Inouye, a new series of protected areas were eventually established in Hawaii: the Hakalau Forest National Wildlife Refuge, and additional sites on Maui and Molokai. That was Mike’s first GAP analysis.

No Way to Run a RailroadIronically enough, his next assignment on the mainland was as director of the California Condor program. “I had more biologists than I had animals of the species,” Mike says, “with a budget 10 times larger than my budget in Hawaii, where I’d been responsible for 30-plus species. That’s when I realized, this is no way to run a railroad. When we’re preventing extinction, we’re in the emergency room. We need to enter the world of preventive care.”

I agree with Mike. Having hiked extensively in the Rockies, I knew that most western protected areas were in the mountains and hosted low biodiversity. My years at the office of Endangered Species had taught me that to save an endangered species you need to staunch the causes of mortality. As a result I knew there was a significant disconnect between our funding allocations and on-the-ground species conservation.

The question was, how to do it? “At that time, the idea of working on multiple species and saving them while still common ran counter to the current thinking,” says Mike.

Along with two co-authors, Mike published his seminal 1987 paper about the new technique of GAP analysis in Bioscience, entitled “Species richness: A geographic approach to protecting future biological diversity.” He also moved to Idaho and began working on a statewide GAP analysis, with help from a National Fish and Wildlife Foundation grant that I approved in 1988. That same year,

Mike Scott was able to establish a national GAP analysis program, later publishing a Wildlife Monograph about the GAP process.

One of his studies was particularly relevant to private working lands. He looked at the distribution and ecology of U.S. protected areas. He found the highest protection was awarded to lands with the highest elevations and lowest

productivity soils.

Mike puts it more bluntly: “We have done a great job of protecting rocks and ice.”

Please return to the blog next week, for our discussion of conservation beyond rocks and ice.

Sign In

Sign In

Sign In

Sign In