The Little Land Trust that Could

By: Amos S. Eno

Posted on:06/12/2015 Updated:01/09/2018The Lemhi Regional Land Trust breaks out.

On June 4th, I took a western swing on my travels for LandCAN, going first to Jackson Hole, Wyoming to visit LandCAN board member Bob Grady and my former National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) board member Jerry Halpin.

From Jackson, I stopped in Bozeman, Montana, where I met with Tim Griffiths and Dave Naugle of the Sage Grouse Initiative and the leadership of the Property and Environmental Research Center before driving south west through Bannock Pass en route to Idaho’s Lemhi Valley, the farthest reaches of the Columbia River Basin where salmon spawn at almost 9,000 feet.

In Lemhi on Wednesday, I was hosted by Princeton classmate Nikos Monoyios and his wife Valerie for a reception with the Lemhi Regional Land Trust (LRLT), which was formed by four local ranchers in this far eastern valley of Idaho up against the Continental Divide. LRLT’s Executive Director is Kristin Troy with whom we will soon be doing a follow-up blog.

What follows is an abridged version of the speech I gave that night as well as a few images from the presentation.

Next year is 2016, the centennial of the National Park Service. We have had one hundred years of progressive conservation in this country dating back to Teddy Roosevelt and Gifford Pinchot, one hundred years when the focus of conservation has been predominantly on expanding public lands and expending 90 percent of tax dollars set aside for conservation (mostly through the Land and Water Conservation Fund) on federal holdings.

Over the breadth of my career, I have reconsidered the pathway for conservation. My eyes were first opened in 1974 when I was sent by the Assistant Secretary of the Department of the Interior to Maheur National Wildlife Refuge in Harney County, Oregon – cattle country – to fire the refuge manager, Joe Mazzoni. Under pressure from metropolitan environmentalists, led by Denzel Ferguson, who wrote Cows at the Public Trough, Governor McCall wanted grazing terminated on public lands? I spent three days with Mazzoni, who was gradually reducing grazing in critical areas. I decided that he was doing a great job. The following Monday at a staff meeting, the Secretary said; “Did you fire him?” “No,” I said, “he deserves a medal!”

Over the breadth of my career, I have reconsidered the pathway for conservation. My eyes were first opened in 1974 when I was sent by the Assistant Secretary of the Department of the Interior to Maheur National Wildlife Refuge in Harney County, Oregon – cattle country – to fire the refuge manager, Joe Mazzoni. Under pressure from metropolitan environmentalists, led by Denzel Ferguson, who wrote Cows at the Public Trough, Governor McCall wanted grazing terminated on public lands? I spent three days with Mazzoni, who was gradually reducing grazing in critical areas. I decided that he was doing a great job. The following Monday at a staff meeting, the Secretary said; “Did you fire him?” “No,” I said, “he deserves a medal!”

In the late 1980s, as Executive Director of NFWF, I gave a grant to Mike Scott to build GIS-GAP analysis technology here in Idaho. His analysis found that Idaho, which is 68 percent federal, has a lot of protected rock, ice, lodgepole pines and high desert on public land, but all of the biodiversity is in the Snake River Basin and other riparian areas, and around Coeur D’Alene on the twenty percent of Idaho’s land that is privately owned.

In the 1990s, I started a NFWF grant program to target private land conservation. We funded Sustainable Northwest (which featured the Lemhi Valley), Blackfoot Project, Malpais Borderlands, Colorado Cattlemen’s Agricultural Land Trust, California Rangeland Trust, Texas Agricultural Land Trust, the creation of Texas Parks and Wildlife’s Private Lands program, which today has over 30 million acres enrolled…And then I was taken out by the Clinton Administration and the initiative disappeared.

In the 1990s, I started a NFWF grant program to target private land conservation. We funded Sustainable Northwest (which featured the Lemhi Valley), Blackfoot Project, Malpais Borderlands, Colorado Cattlemen’s Agricultural Land Trust, California Rangeland Trust, Texas Agricultural Land Trust, the creation of Texas Parks and Wildlife’s Private Lands program, which today has over 30 million acres enrolled…And then I was taken out by the Clinton Administration and the initiative disappeared.

By 2000, I was convinced that the future market for conservation was no longer going to have a public lands focal, but would evolve to private lands and leadership by the private sector. So in 2000, I set up my own foundation, LandCAN, and started to build a suite of websites, which today are the largest conservation innovation platform on the internet in the U.S. All are targeted to empower private land owners.

There are some 13 million land owners in the U.S., 2.2 million farmers and ranchers, and 10.7 million forest owners. Each family has unique circumstances and needs. You can’t cookie cut conservation for landowners, nor ram programs down their throats. Each family requires custom treatment.

How do you approach landowners? Through federal agencies’ outreach? No! Through environmental groups telling land owners what to do with their land and pushing more regulations? I think not.

You know the Lao Tzu expression about teaching a man to fish, but I am going to give you a quote from Confucius: “If you think in terms of a year, plant a seed; if in terms of ten years, plant trees; if in terms of 100 years, teach people.”

That is what we do. We do not tell land owners what to do, but we do provide the full spectrum of programs, goods and services that will help them become involved in conservation.

Nothing more embodies the ugly in today’s world than the hijacking of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) by a group of former fringe environmental groups such as the Center for Biological Diversity, Defenders of Wildlife and the Sierra Club Foundation, all of which have grown rich by petitioning to list hundreds of species and use the listing process to sequentially shut down the forest products industry in the West (accomplished), long-eared bat to do the same for Eastern and Midwestern forests, the oil and gas industry in our prairie states, and of course the cattle industry throughout the West.

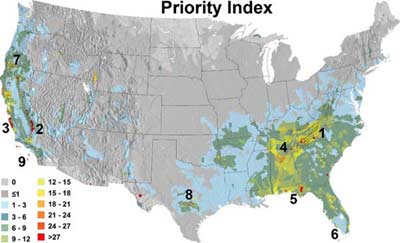

We have created a website recently, the Conservation Habitat Management Portal, to help with two species – one listed as threatened and the other proposed for listing - whose wide ranges are overwhelmingly impacting private landowners: the lesser prairie chicken (Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, and New Mexico) and the greater sage-grouse, which inhabits eleven Western states from California to the Dakotas.

We have created a website recently, the Conservation Habitat Management Portal, to help with two species – one listed as threatened and the other proposed for listing - whose wide ranges are overwhelmingly impacting private landowners: the lesser prairie chicken (Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, and New Mexico) and the greater sage-grouse, which inhabits eleven Western states from California to the Dakotas.

I think the ESA can be strengthened and reformed by expanding Section 6, the portion of the Act that provides grants to states to assist in recovery of listed species. Section 6 has never been amended in its 43 years of existence, and I believe the role of states in listing and recovery should be substantially broadened to reflect the on the ground successes that are occurring across the West and the rest of our states.

The general public does not recognize a number of important changes that have occurred. In the mid-1990s, Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt, in a misguided effort, removed the Research Division from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which has subsequently handicapped the Service’s ability to conduct research. In today’s world, states have better on the ground capacity for research, as well as better management, better outreach to landowners, and better cooperation with private industry.

The example of the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies’ (WAFWA) recovery plan for the lesser prairie chicken provides a beacon of success emblemizing state initiative and success in orchestrating recovery efforts; in just a year they have raised $43 million for recovery, have 171 companies in cooperative agreements, have set aside 10 million acres of land, and have 97 thousand acres in long term conservation.

Comparable success is being achieved across Western states for sage grouse. In Colorado’s Gunnison County, 97 percent of private land is enrolled in conservation agreements. This represents the future pathway for orchestrating species recovery, as you have witnessed here in this valley with the leadership role of landowners such as our hosts, the Monoyios’, working in cooperation with the Lemhi Regional Land Trust and Idaho Fish and Game on chinook salmon habitat restoration. The model for conservation success is clearly outlined in contemporary partnerships such as these.

Feedback

re: The Little Land Trust that CouldBy: Diana Gennett on: 06/18/2015Than you for writing the speech and posting it her on the PLN. It has given me information I did not now on how some program disappeared. Then given me new ones to follow and learn from to pass information on to landowners I work with.

Sign In

Sign In

Sign In

Sign In